Story at a glance

-

From lab to land

Breaking long-held stereotypes

-

Africa's regional researchers

Delivering animal vaccines for their neighbors

-

Towards Stronger Communities

Researchers supporting the industries around them

As she hops aboard a plane bound for the vast rural reaches of her native Australia, Aleta Knowles couldn’t be further from the sterile stereotype of a research scientist.

There’s no fraying labcoat – just sturdy, outdoor gear – and the huge microscopes and artificial lights are switched out for a reliable laptop and the sweeping vistas of New South Wales.

“It’s a very big country, so it’s an early start for us, flying out to a remote location where the sheep are,” she explains.

“Then it takes a lot of people to handle the animals and get the kind of data we need. Then it’s animal wrangling, paper shuffling, recording a lot of information … at the end of it, we do it all in reverse and pack up and fly back to Sydney.”

Aleta’s research is in developing new vaccines for sheep and cattle. It’s a career she loves, but one subject to the extremes of this vast, elemental continent.

“There are always challenges in research – it’s completely unpredictable,” she explains. “I’ve had studies that have been wiped out by cyclones, and I’ve had studies that have been wiped out by bush fires.”

Aleta and her team have had to pick up the pieces and start again any number of times, but – like many researchers – this animal lover is motivated by the practical impact of her work.

“The research I do makes things and it puts them in the hands of veterinarians,” she says.

“And I love it when they tell me they’ve used a product I’ve developed and they like it – it means I’m doing my job well. And ultimately, healthy sheep produce more meat, more wool and more milk, so that’s where I direct my research.”

The research I do makes tools and puts them in the hands of veterinarians”

Aleta KnowlesAnimal medicines researcherIf our stereotype of a research scientist is a little wide of the mark, then the public understanding of the process of developing a new medicine is even wider.

“It takes a very long time to get a medicine from what you might call the eureka moment to actually putting it in the hands of farmers,” Aleta explains.

She’s one of a cast of thousands, potentially working over the course of a decade or more to bring a new medicine to market.

“Once we know a product can be manufactured and it’s safe, that’s when I get my hands on it to determine whether it’s clinically viable.

“What does it look like when we use it with animals? Does it do what we say it will do, and does it provide value to the farmer? That’s where I work.”

We find this same commitment in Belgium, where we visit a lab that’s a little closer to our expectations. Latex, protective clothing and powerful electron microscopes abound (without a cyclone in sight).

Director of new product transfer and development Francis is a distant colleague of Aleta’s, working on vaccines to better protect our companion animals. He’s further back in the development timeline Aleta sketched out, but his focus on the outcome is the same.

“I know every new molecule I bring from development to production will have, as a consequence, an animal that may be cured or more healthy.”

Francis is particularly interested in the wider, societal benefits of his work.

“Healthy pets mean healthy humans, and in that context we need to work towards treating the many disease that occur in these animals.”

Africa’s regional

researchers

Delivering animal vaccines for their neighbors

This same ‘big picture’ motivation is evident in Nicholas Vitek, a Canadian vaccines researcher now based in Nairobi, Kenya. He’s part of The International Livestock Research Institute, based in East Africa where it works to fight the diseases that blight the communities of the region.

Many of its employees have grown up witnessing the impact of these diseases first-hand.

Our goal is to perform research and find solutions for diseases or problems that affect livestock, and directly for smallholders in the developing world, so we focus our attention mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, but we also have projects in Asia and other parts of the world.”

Nicholas Vitek, Animal vaccines researcherHis colleague Naftaly Githaka is researching new vaccines to combat East Coast Fever (ECF), the deadly livestock disease that’s thought to kill an animal every 30 seconds in the region. He outlines how this research is vital to the fortunes for the countless communities who depend upon their livestock.

“This disease has a major impact on smallholder farmers who want to use cattle and especially the dairy sector as a means of livelihood. So, a vaccine would go a long way to decrease mortality, increase production, but also increase the value of these cattle that are being vaccinated.”

The aquaculture industry being so new, there’s so much innovation. There’s lots of new technologies coming in, lots of new species and you’re interacting not only with farmers, but the bigger producers, retailers and consumers – it’s very exciting.”

Ben Perry,Fish medicines researcherResearchers supporting the industries around them

So tightly bound is the health of animals with the economic health of communities that it’s inescapable.

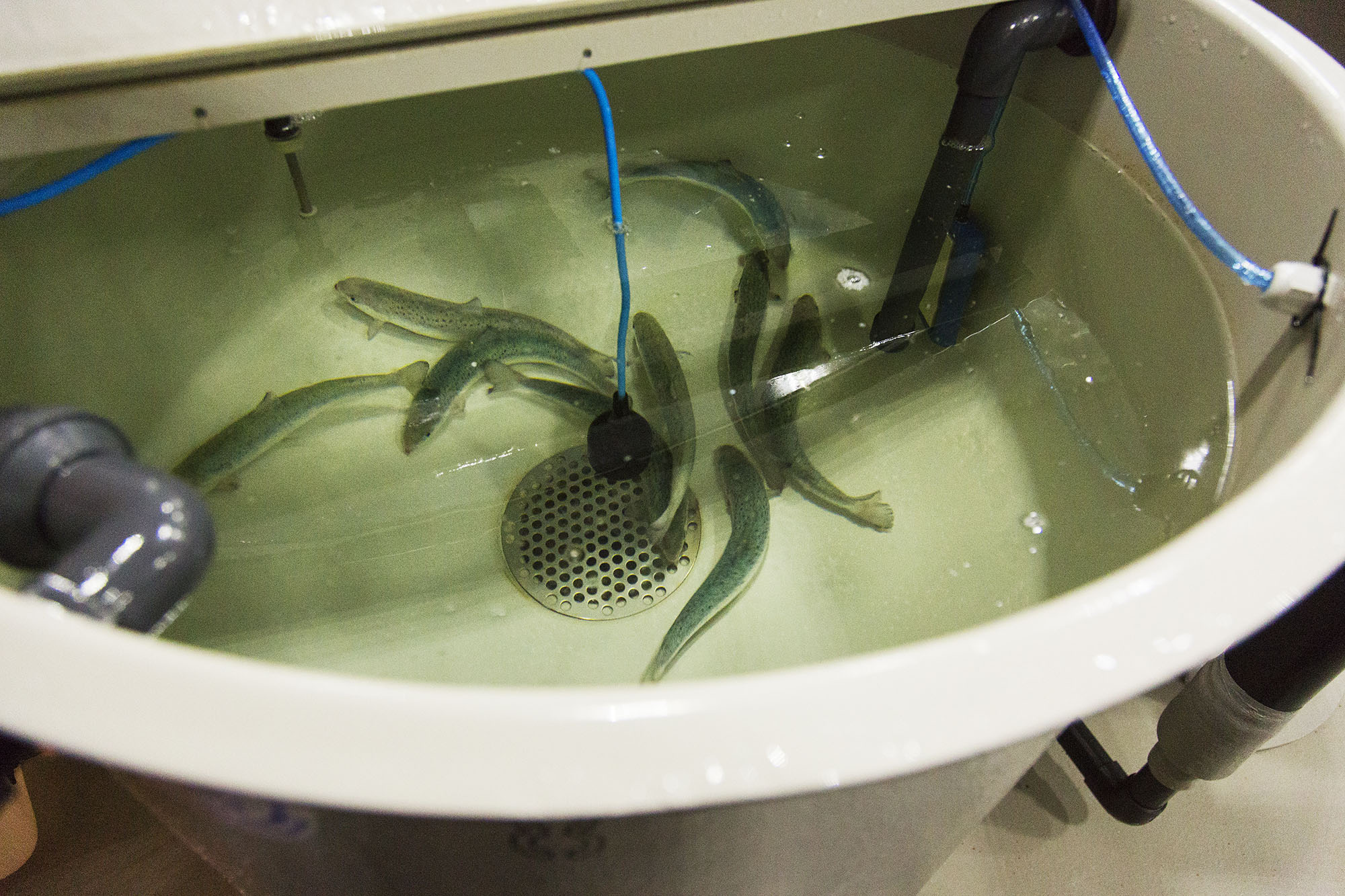

Ben Perry, a marine biologist at the leading edge of the relative young and booming aquaculture industry, is also acutely aware of the impact his research has on the health of the planet.

“We hope a new product will have a positive impact on everyone concerned,” he says. “From the ability of the farmer to produce more salmon the ability for that environment to be improved or more sustainable, for example.”

His purpose-built lab overlooks the pristine waters of Ardtoe on the west coast of Scotland, two hours from the nearest major airport.

During the height of the summer, nearby hotels bustle with nature enthusiasts while Ben’s team ride out to salmon farms to witness their research in action.

“The aquaculture industry being so new, there’s so much innovation. There’s lots of new technologies coming in, lots of new species and you’re interacting not only with farmers, but the bigger producers, retailers and consumers – it’s very exciting.”

Ben echoes Aleta’s sentiment about the investment in developing a product and outlines a process that can take between three and seven years.

“The trial process brings together a huge body of people with varied expertise,” he explains.

“Initially, we have a very large research and development programme, which identifies the kind of medicines we might be able to use, and then that feeds into a smaller-scale programme here at Ardtoe, where we look at the fish health and welfare aspects of that medicine – whether it’s efficacious and whether it could potentially impact the environment.”

All of our researchers have had their share of successes and failures. Lessons have been learnt the hard way, and products left behind, but the wider ambition remains.

“I love what I do,” says Aleta from her Sydney HQ.

“All our lives are touched by animals, and by working towards improving the lives of animals, we’re also improving the lives of people.”

“It’s our ethical responsibility to ensure animals health and welfare standards are met to the best of our ability,” she says.

In all of these countries and communities, the lives of veterinarians, animals and those who depend upon them both are closely interwoven.

While you’d expect vets around the world to take pride in their care for their animals, it seems the care they provide to their communities – however international – is equally valuable.

Spotlight: China’s veterinarians embracing new innovation

The extraordinary growth of China has been one of the defining economic stories of recent decades. It’s lifted millions of people out of rural poverty and swelled the ranks of a middle class who’ve made the country the globe’s biggest consumer of meat.

It’s now surpassed the US as the world’s biggest pork producer, and so operations here in the Chongqing area in the western part of the nation are clearly a very different farming operation than rural Australian outfits and Kenyan smallholders.

Disease control here is reliant on systematic approaches.

“We have a veterinary platform to provide us with all the necessary information, such as the immunisation procedures and the treatment regimen tables we need to make judgment on disease types,” explains

“Medications will be administered based on the observed symptoms. If we cannot make the judgment call, we will enter the disease information into a software system where the information can be shared with veterinarians who then will advise us on how to treat the diseases. Through the big data platform, you can basically expect a problem to be solved within a few hours.”

The use of big data to solve these practical problems has become a national priority for China. In 2016, an official state notice highlighted the strategic importance of big data in improving healthcare for China’s 1.3bn people.

In animal health, the numbers don’t lie, and they’re calling for a focus on vaccination, as veterinary director Zhang Renna explains.

“The breeding density of large-scale farms is very high, so some contagious diseases, if not properly controlled, will cause many pigs to die given their fast spreading speed, meaning the farming companies incur huge losses.

“We have always adhered to the philosophy that prevention, rather than treatment is the way forward. It is too late to reverse the situation if we just wait until the disease comes.”

the long walk towards

rabies eradication

Next story

Other stories

- A Lifetime of Mutual Care

- Health, Husbandry and Heritage

- Pride in Profession

- From Lab to Land

- The Long Walk towards Rabies Eradication

- Healthy Animals Drive Economic Growth

- Responsible use: the responsibility of us all

- Innovation for Sustainable Production

- Farming to feed a growing world

- Protecting Animals Protects People